Could Australia’s Recent Radiation Scare Happen in Canada?

Note: This article was originally published in Healthy Debate. Republished under the creative commons licence with minor revisions approved by the author.

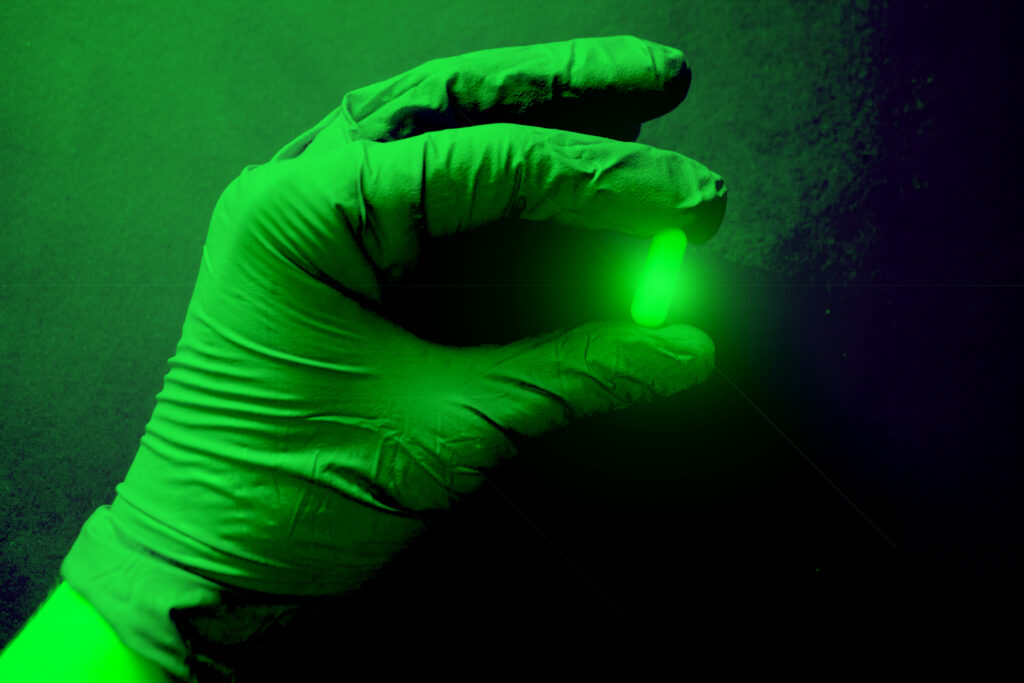

The massive search in Western Australia in February 2023 for a highly radioactive ceramic disc that had fallen off a truck drew worldwide attention. Amazingly, the cylindrical capsule, about half the size of a dime across and five stacked dimes high, was found. Could a similar incident happen in Canada?

The disc fell out of a fixed radioactive gauge device somewhere along its more than 1,300 km truck ride from a Rio Tinto mine site in Newman en route to Perth. It is believed that vibrations from the truck ride loosened an outer screw on the device, allowing the capsule to drop out of the screw hole and onto the road.

The tiny capsule was found using a gamma-ray detector while driving slowly along the road. Australian government officials described it as trying to find a needle in a haystack.

Standing one metre away from the radioactive capsule for one hour would expose a person to the same amount of radiation as about one year of average natural background radiation in Canada. However, according to an ABC News report, Angela Di Fulvio, an assistant professor of nuclear engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, said, “prolonged close exposure to the capsule – for instance, if someone picked it up and put it in their pocket – could cause severe, and even potentially deadly, health effects within hours.”

In1999, a welder at the Yanango hydroelectric plant in Peru experienced awful health effects similar to those described by Di Fulvio above. The welder picked up what looked like a metal pellet attached to a braided steel cable. Not realizing what it was, the welder put the object in his right back pocket and continued to work. What he had picked up was, in fact, a highly radioactive industrial radiography source that had come out of its protective housing. Although the radioactive source was in the welder’s pocket for only about 6 1/2 hours, his fate was sealed. Despite six months of hospitalization and intense supportive care, the welder suffered progressive ulceration and infections in his right thigh and eventually had to have his leg amputated.

“Prolonged close exposure to the capsule . . . could cause severe, and even potentially deadly, health effects within hours.”

Canada is a nation rich in natural resources, with associated industrial activities such as mining, fossil fuel extraction, and the laying of pipelines. These activities commonly use radioactive gauges (also called sealed-source devices) for quality assurance testing, such as measuring water concentration, fluid levels, and material density, or checking for cracks in metal welds. Sealed-source devices are also commonly used for sterilizing medical equipment, food irradiation, and radiation therapy.

Radioactive gauges can be permanently attached to a structure, or they can be portable. While the size of fixed gauges varies depending on what they are used for, portable gauges are generally the size of a large lunch box.

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) regulates sealed-source devices and tracks them through its Canadian National Sealed Source Registry.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) classifies radioactive sources as “extremely dangerous” (Category 1) [1] to “most unlikely to be dangerous” (Category 5),[2] depending on the radioactive source. The lost Australian radioactive pellet was categorized by IAEA as “unlikely to be dangerous,” (or Category 4) [3] – unless, of course, you put it in your pocket.

There were more than 70,000 registered radioactive sources in Canada in 2020, with about 90% of them being classified as dangerous to humans (Category 1, 2, or 3).

CNSC requires sealed-source device licensees to report lost or stolen devices. Immediate measures are taken to investigate and locate them, especially for higher-risk devices. From 2008 to 2022, CNSC reported 37 lost and 27 stolen sealed-source devices. Except for one, all contained sources that were unlikely to be dangerous. Only nine devices were recovered, including the one containing a dangerous source. There have been no reports of radiation-exposure injuries related to these incidents.

In portable sealed-source devices, the radioactive source is stored in a gauge device that blocks radiation from escaping. The source comes out only when the device is in use, and there are strict operating procedures to protect workers, the public, and the environment.

An email I received from the CNSC communication staff (on March 31, 2023) about lost sources in Canada said, “To this day, there has never been a reported event to the CNSC that involved the loss of a sealed source after it came out of the radiation device.” However, as was illustrated by what happened in Peru, there have been incidents that demonstrate the disastrous effects of picking up an unsecured radioactive source, which can look like an innocuous metal pellet.

In general, minimizing exposure time and staying at least two metres away from a suspect unshielded source will be protective. In the unlikely event that you recognize a loose radioactive source, stay away, warn others not to approach or handle the source, and call the local authorities. The police and local hazmat teams should know how to assess and manage the situation.

[1] IAEA Safety Standards for protecting people and the environment, Categorization of Radioactive Sources (Safety Guide No. RS-G-1.9), page 32.

[2] IAEA Safety Standards for protecting people and the environment, Categorization of Radioactive Sources (Safety Guide No. RS-G-1.9), page 33

[3] Written submission from CNSC Staff, page 2.

Healthy Debate publishes journalism (clear, captivating op-eds and feature reports) about health care in Canada by the people whose lives it touches the most—from physicians, patients, and caregivers to health journalists, academics, and advocates. Their unique focus on giving a platform to health-care insiders allows them to provide detailed coverage of the inner workings—and dysfunctions—of this important sphere of Canadian society. They are a forum where the public can learn about, discuss, and debate health care in Canada and, importantly, imagine what it could become.

Dr. Sandor Demeter

Dr. Sandor Demeter

Sandor is a nuclear medicine and public health physician and associate professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba. He served two terms as a commission member with the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC), as well as two terms as a member of the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) Committee 3 (medicine). He is a member of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) Health Technology Expert Review Panel.

Sandor recently completed a Fellowship in Global Journalism at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto.

Do you want to read more articles like this?

The Bulletin is published by the Canadian Radiation Protection Association (CRPA). It’s a must-read publication for radiation protection professionals in Canada. The editorial content delivers the insights, information, advice, and valuable solutions that radiation protection professionals need to stay at the forefront of their profession.

Sign up today and we’ll send you an email each time a new edition goes live. In between issues, check back often for updates and new articles.

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe now!

Subscribe

Dr. Sandor Demeter

Dr. Sandor Demeter