Let’s Be Clear: Overcoming the Negativity Bias

Like it or not, writing clearly and effectively is becoming an increasingly important skill in a science career. Unfortunately, writing doesn’t come easily for many scientists. The Let’s Be Clear series provides practical advice to help Bulletin readers write with more confidence.

In the last article, we explored the communication process and the writer’s role in that process. In this article, we’re talking about our built-in negativity bias and suggesting some ways to overcome it in writing.

The communication process

As we discussed in the last article, written communication is a process that involves a number of steps:

- The writer comes up with an idea (the message) they want to share with others.

- The writer encodes (writes) their message to share their idea.

- The reader decodes (reads) the message and tries to understand what the writer was trying to share.

- Ideally, the reader will have an opportunity to provide feedback to the writer to confirm that they have decoded (understood) the message correctly. If there was something in the message that the reader didn’t understand, that feedback may take the form of questions asking for more information.

In this ideal situation, the cycle of encoding, decoding, and feedback continues until the message is understood correctly. Unfortunately, written communication is often a one-way process, so if the writer doesn’t do their job well, the process breaks down and is not successful.

Up to 80% of communication is non-verbal

Another shortfall of written communication is that it lacks many of the visual cues we rely on to interpret what someone is saying. Experts estimate that, when we’re talking with someone face-to-face, 60% to 80% of communication is non-verbal.

When we are communicating through writing, we have to rely on fewer communication cues, which means we are more likely to fill in the missing information for ourselves.

We have a built-in negativity bias

When intentions are not clear, people tend to jump to conclusions. We also tend to assume the worst. We have a built-in negativity bias that makes us more likely to perceive things negatively.

When things go wrong, most of us are more generous with ourselves than we are with others. For example, when someone else does something that annoys us, we tend to blame them. (He cut me off in traffic. What a jerk!) On the other hand, when we do something wrong, we tend to blame circumstances. (Oops, I just cut that guy off. The lane closure came up on me too quickly!)

And it’s not just a perception. Researchers have determined that there’s greater neural processing in the brain—a surge of activity—in response to negative stimuli.

Our negativity bias is likely a result of evolution

Earlier in human history, paying attention to bad things—threats—was literally a matter of life or death. Those who were more attuned to danger were more likely to survive and to pass on the genes that made them more attentive to danger.

Today, the part of our brain that once alerted cave dwellers to potential dangers is what makes us hypersensitive to negativity. Before we get too upset about an email that we perceive to be overly critical, we need to stop and ask ourselves if our reaction is entirely warranted. Perhaps the other person didn’t mean to sound so critical. Perhaps we’re overreacting.

We also need to check our own words to be sure we’re not giving the wrong impression.

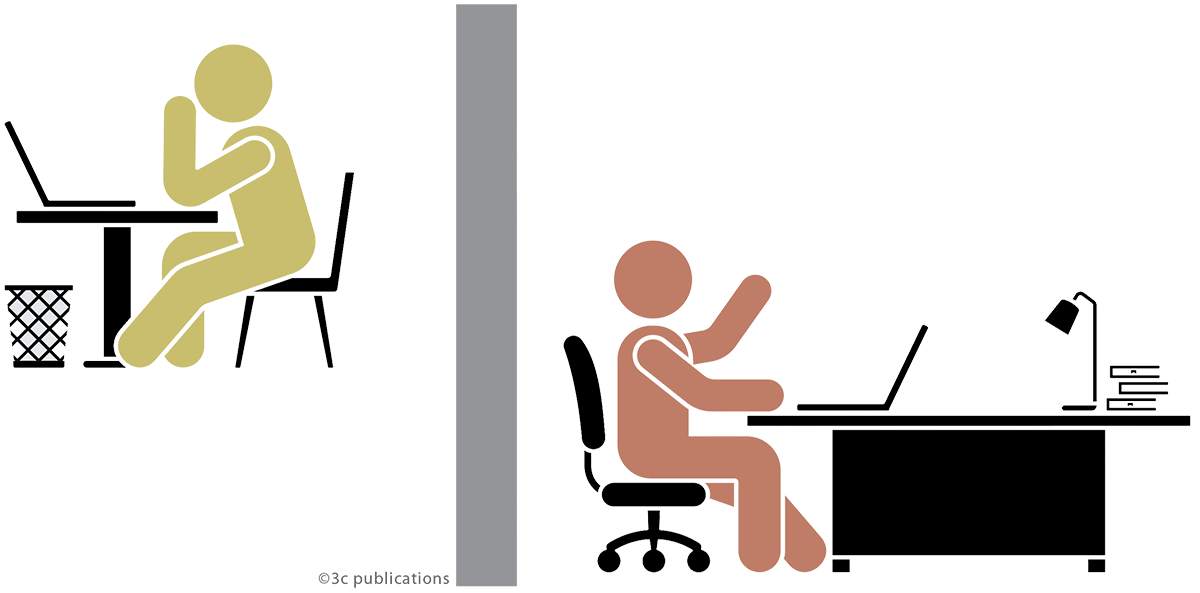

It’s easier to say negative things when we can’t see the person receiving the message

In writing, people tend to be even less guarded and more negative. When we can’t see the response of the person receiving our message, it’s easier to say things we wouldn’t say in person—complain, express anger, or even insult one another.

And that negativity goes both ways. People receiving written messages tend to interpret them more negatively than the sender intended. Recipients of an email that’s intended to convey positive emotions tend to interpret the message as emotionally neutral. An email with a slightly negative tone is often interpreted as being much more negative.

In her book Unsubscribe, Jocelyn Glei puts it like this: “[E]mail really is like kryptonite when it comes to expressing positive emotions—it’s as if every message you send gets automatically downgraded a few positivity notches by the time someone else receives it.”

The negativity bias also happens in text messages. If you’re ambiguous in a text, people will often interpret the message negatively. In a 2016 paper titled “RU mad @ me? Social anxiety and interpretation of ambiguous text messages,” the authors discussed interpretation bias, which they define as the tendency to interpret ambiguous situations negatively.

For example, if a friend texted you the day after you attended a party and said, “I heard about last night,” would you assume they had heard something good about the party or that they had heard about something embarrassing you had said or done at the party? The authors’ research suggests most people would interpret this as implying something negative.

Try to eliminate ambiguity in your writing

“It’s not enough to write so that you can be understood—you should write so that you cannot be misunderstood.”

I’m not sure who originally said this, but it’s one of my mantras as a communicator.

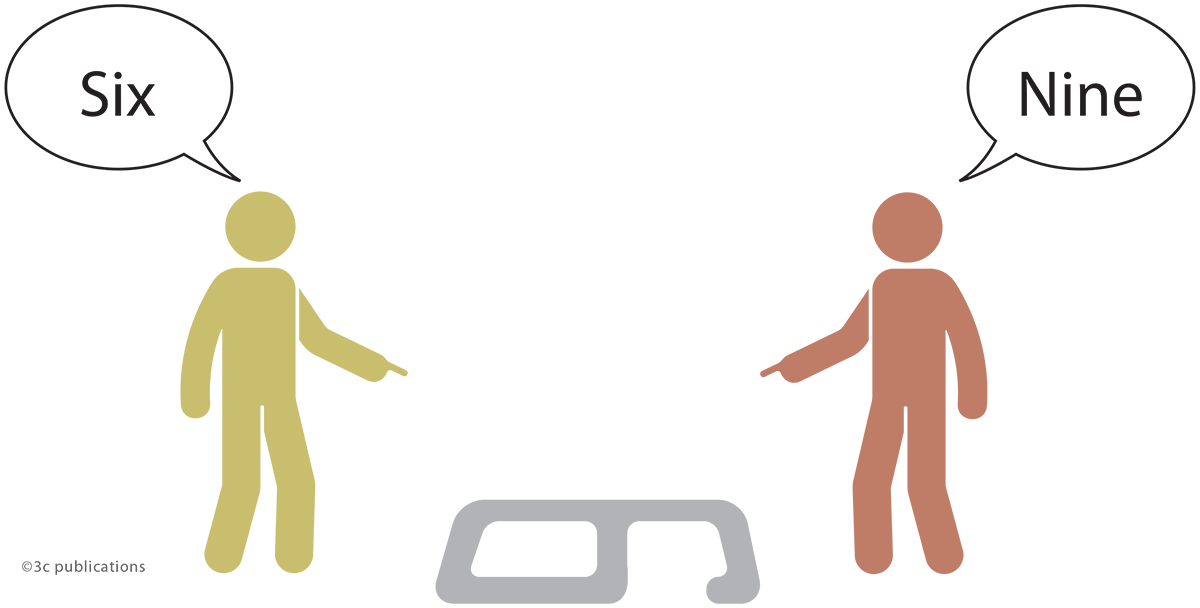

As the author, you know what you’re trying to say, so you assume others will easily be able to understand your message. The problem is that different people read with different lenses.

Follow these simple guidelines for communicating more clearly

What can we do to improve the odds of our written messages being understood the way we intended them to be?

- Consider your audience and your purpose.

- Keep your messages clear, simple, and easy to understand.

- Break your messages into small, easily digestible pieces.

- Use descriptive headings to highlight main points and signal topic changes.

- Proofread your messages before you send them!

Ultimately, this all comes down to writing clearly and reading carefully. And remember, we all make mistakes. Try to be understanding and give people the benefit of the doubt.

Résumé : Soyons clairs : remédier aux partis pris négatifs

Lorsque les intentions des gens manquent de clarté, on tend à sauter aux conclusions et à s’attendre au pire. Nous avons tous des partis pris négatifs intrinsèques qui nous rendent plus susceptibles de percevoir les choses négativement, et à l’écrit, les gens ont tendance à être encore plus négatifs.

La série « Let’s Be Clear » donne des conseils pratiques pour aider les lecteurs du Bulletin à écrire avec plus de confiance. Dans ce numéro, nous abordons nos partis pris négatifs intrinsèques et suggérons des moyens d’y remédier par l’écriture.

Michelle Boulton

Michelle Boulton is a clear communication specialist who uses clear (plain) language and design to help clients translate complex information into content everyone can use and understand. She and her team have been helping CRPA produce the Bulletin since 2007. For more information about Michelle, please check out her LinkedIn profile.

Do you want to read more articles like this?

The Bulletin is published by the Canadian Radiation Protection Association (CRPA). It’s a must-read publication for radiation protection professionals in Canada. The editorial content delivers the insights, information, advice, and valuable solutions that radiation protection professionals need to stay at the forefront of their profession.

Sign up today and we’ll send you an email each time a new edition goes live. In between issues, check back often for updates and new articles.

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe now!

Subscribe