Canada’s Radioactive Pioneers – Part 2: Radon’s Role in Worker Health and Safety

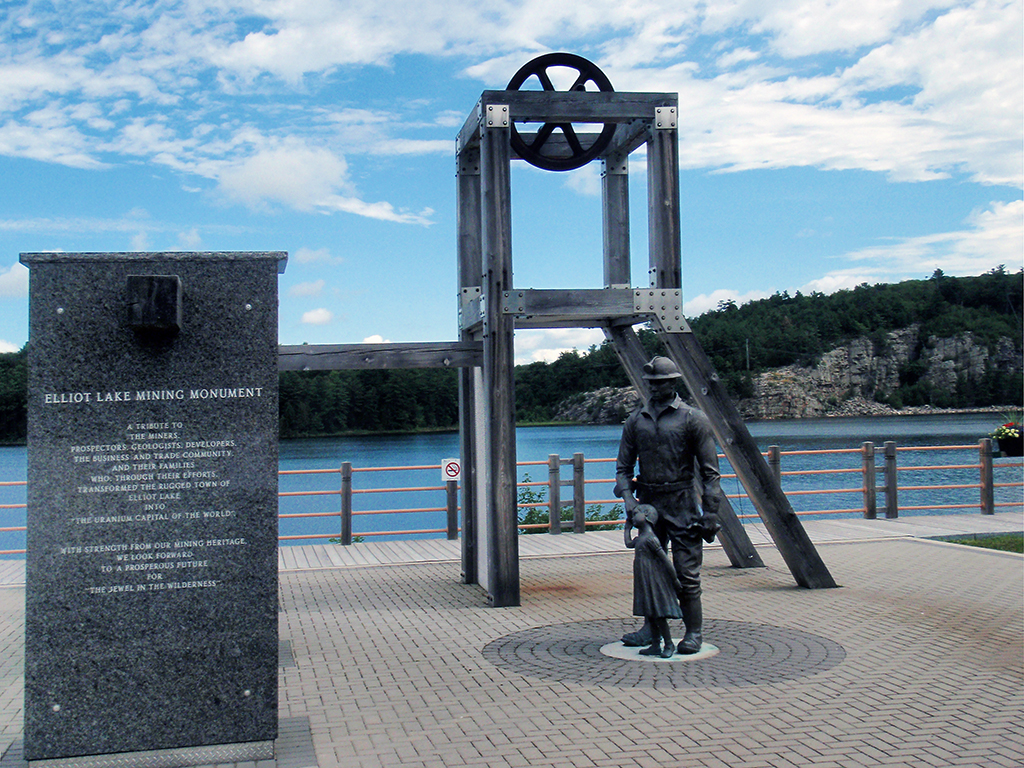

Mining Monument, Elliot Lake (photo by XeresNelro)

In the first article of this series, we explored the life and legacy of Harriet Brooks, one of Canada’s radioactive pioneers. Ms. Brooks was the first person to name radon, but she was far from the last person in the uranium-rich country of Canada whose life was touched by the invisible, deadly gas.

In this second article, we spoke to John Perquin about the miners of Elliot Lake and radon’s role in a pioneering moment for Canada’s worker protection laws.

Uranium mining in Canada today

Uranium is big business in Canada. Currently the world’s second-largest producer, Canada puts out approximately 13% of the world’s uranium, bringing in $800 million per year and employing over 2,000 Canadians at uranium mine sites.[1]

As we all know, where there is uranium, there will be radon. Nowadays, radon levels in uranium mines are carefully monitored and tightly controlled so that uranium mine workers aren’t at an increased risk of lung cancer.[2] However, like so many developments in worker health and safety, this wasn’t always so.

Radon risks in Elliot Lake

John Perquin, who is now retired from his role as the assistant to the international secretary-treasurer, United Steelworkers, shares his insights.

“The lessons learned and still to learn from Elliot Lake are not just related to the workplace,” he says. “As tragic as the many needless workplace-related deaths were, people also died because of exposure to radon in their homes. In the late 1970s, Elliot Lake modified its building code to include the requirement of a fully functioning radon mitigation system in each newly constructed home. The merits and need for such a system were widely known and understood by the residents of Elliot Lake at the time.”

The uranium boom and worker neglect

Uranium mining in Canada boomed in the 1950s, fuelled by Cold War demand from the US. The hot spot at the time was Elliot Lake, which provided most of the world’s uranium and was known as the Uranium Capital of the World. With a prospective “uranium rush,” mines were established in record time and amongst frantic competition. From late 1954 through 1956, 12 uranium mines were established in Elliot Lake.[3] In such a booming industry, however, worker health and safety were left behind.

Growing health crisis among miners

By the mid 1960s, Elliot Lake miners began falling ill with silicosis, lung cancer, and other lung diseases. The mining companies refused any financial support to afflicted miners, blaming the illnesses on the workers’ smoking habits or improper use of safety equipment.

The 1974 Elliot Lake Strike

Frustration among the miners grew, reaching a boiling point in 1974 when the miners discovered that a Ministry of Health study presented in Bordeaux, France, confirmed their illnesses were caused by conditions in the mines.[4]

On April 18, 1974, the Elliot Lake miners launched a wildcat strike with a list of demands that included 54 health and safety concerns to be addressed. The strike lasted a little over two weeks, but the impact of their job action is still being felt today.

The Ham Commission and worker protection laws

In what would become known as the Ham Commission, Ontario’s Premier ordered an investigation into the working conditions in the mines. The report issued by the Ham Commission in 1976 identified lung cancer and ionizing radiation among many other concerns and outlined the need for a new structure of laws to protect workers. This resulted in the Occupational Health and Safety Act, which was the first and most comprehensive law to protect workers in Ontario.[5]

The Radiation Safety Institute of Canada (RSIC) was also established as a result of the tragic mismanagement of risk in Elliot Lake, with the mission of protecting workers from excessive radiation exposure to avoid future disaster.[6] This includes running a dosimetry service to monitor underground uranium miners for exposure to radon progeny and long-lived radioactive dust.

“The most important thing to come out of mines is the miner.”

~ Frederic LePlay, French sociologist and inspector general of the mines of France in the late nineteenth century

Ignored warnings: radiation knowledge from the start

One of the most striking revelations of the Ham report, at least to a modern reader working to protect the public from the hazards of radon, is that the risk posed by radiation in the Elliot Lake mines was known from the very beginning.[7] An internal advisory committee met regularly from 1956 through 1964 to gather information from other countries, and was advised by Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd. Radiation in the mines was measured and recorded from 1957 onwards. From the early 1960s, a committee worked to set up occupational records in order to assess the “present and future lung cancer risk in uranium miners.”[8] These records formed the Nominal Roll of Uranium Miners, with estimates of mortality by cause of death. Reports were made to the Ministry of Health during the period of 1955 to 1970, and then updated in 1974 to include deaths from 1971 to 1972. All the while, miners continued working—and getting sick—completely unaware.

When the findings of the Ministry of Health report became known to the miners, not only did the workers strike, but they also expressed their deep feelings of mistrust and betrayal. Union leaders stated at the time, “we have been led to believe through the years that the working environment in these mines was safe for us to work in. We have been deceived.”[8]

The Miner’s Memorial is a tribute to the mining history of Elliot Lake, ON. This part is a tribute to all the miners who died as a result of working in the Uranium Mines. (photo by Selflearner1)

Failing public awareness: radon in Canadian homes

While it is encouraging to know that workers throughout Canada are now much better protected from radiation and other hazards, when it comes to radon, uranium miners are not the only ones at risk. Indeed, the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) now proudly proclaims that today’s uranium workers “have lower radon exposure in the workplace than in their homes.”[9] So, while these workers are now well protected, the Canadian public all too frequently faces one of the same challenges the Elliot Lake miners faced 50 years ago—ignorance of the risk.

Despite the formation of the National Radon Program in 2007, and despite the continued efforts of a nationwide network of diverse and dedicated stakeholders, too many Canadians remain ignorant of the risks posed by radon in their homes. In certain cases, the situation can feel an awful lot like history repeating itself.

Unheeded warnings in Manitoba

In a 1992 report commissioned by the Manitoba government to investigate radon levels across the province, the authors caution that “the highest mean radon concentrations were found in Dauphin and Morden, where mean ground-floor concentrations provide the same risk of lung cancer as smoking a package of cigarettes per day. The residents of those towns should be warned as soon as possible of the risk of radon and urged to test their homes and to reduce the radon concentrations if necessary.”[10] Thirty-five years later, no action has been taken by the agency that commissioned the report. How many lives have been lost in the interim, with residents completely unaware of the danger lurking in their homes?

Learning from the past—educating the public today

As John Perquin reflects on the lessons from the past, he shares his concerns regarding the current situation with radon across Canada.

“Canada lacks a comprehensive program that helps its citizens understand the effects of radon exposure and its sources, such as their own homes, and how to mitigate against those exposures,” he says. “There are patchwork programs here and there that are doing their best to fill the void, but frankly, it is not enough. Just because radon is a silent and invisible gas does not mean we should be silent and invisible. Until such time as the government steps up and does its part, we who understand have an obligation to educate.”

His statements are in line with the Ham Commission report, which phrased it well: “The Commission sees no excuse for not telling working people the truth, however difficult and imperfect that may be.”[8]

The same may be said for all Canadians; those in a position to spread awareness and information about radon must do everything in their power to do so, to help make all Canadians aware of the risks and take the first step toward protecting themselves.

References

[1] Natural Resources Canada. (n.d.). Uranium in Canada. https://natural-resources.canada.ca/energy-sources/nuclear-energy-uranium/uranium-canada.

[2] Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission. (2012, March). Radon in Canada’s uranium industry [Fact sheet]. Government of Canada. https://www.cnsc-ccsn.gc.ca/eng/resources/fact-sheets/radon-fact-sheet/#risks

[3] City of Elliot Lake. (n.d.). Uranium mining. https://www.elliotlake.ca/en/recreation-and-culture/uranium-mining.aspx#The-Ontarian-Uranium-Rush

[4] TV Ontario. (2023, November 9). Enough hot air, we want fresh air: How a wildcat miners’ strike helped change Ontario labour law. https://www.tvo.org/article/enough-hot-air-we-want-fresh-air-how-a-wildcat-miners-strike-helped-change-ontario-labour-law

[5] Elliot Lake Today. (2023, July 3). How a wildcat mine walkout in Elliot Lake led to better health and safety. https://www.elliotlaketoday.com/local-news/how-a-wildcat-mine-walkout-in-elliot-lake-led-to-better-health-and-safety-9501940

[6] Radiation Safety Institute of Canada. (2024, July 16). Honouring the Elliot Lake miners: 50th anniversary of the wildcat strike – A legacy of safety. https://radiationsafety.ca/honouring-the-elliot-lake-miners-50th-anniversary-of-the-wildcat-strike-a-legacy-of-safety/

[7] Ontario. Royal Commission on the Health and Safety of Workers in Mines. (1976). Report of the Royal Commission on the health and safety of workers in mines (Commissioner: James M. Ham). Ministry of the Attorney General, 76. https://archive.org/details/39091310130152/page/76/mode/1up

[8] Ontario. Royal Commission on the Health and Safety of Workers in Mines. (1976). Report of the Royal Commission on the health and safety of workers in mines (Commissioner: James M. Ham). Ministry of the Attorney General, 77. https://archive.org/details/39091310130152/page/77/mode/1up

[9] Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission. (2012, March). Radon in Canada’s uranium industry [Fact sheet]. Government of Canada. https://www.cnsc-ccsn.gc.ca/eng/resources/fact-sheets/radon-fact-sheet/

[10] Yuill, G. K. (1992). A survey of radon concentrations in Manitoba outside Winnipeg: Report to Manitoba Environment.

Erin Curry

Erin Curry

Erin is a mechanical engineer who previously ran her own building inspection and radon measurement firm. She is currently the regional director of the Canadian Association of Radon Scientists and Technologists (CARST). She also serves as project lead for the Take Action on Radon project. Erin brings a wealth of knowledge and practical experience to support CARST members. Based near Montreal, QC, Erin is the French-speaking contact for all CARST initiatives.

Do you want to read more articles like this?

The Bulletin is published by the Canadian Radiation Protection Association (CRPA). It’s a must-read publication for radiation protection professionals in Canada. The editorial content delivers the insights, information, advice, and valuable solutions that radiation protection professionals need to stay at the forefront of their profession.

Sign up today and we’ll send you an email each time a new edition goes live. In between issues, check back often for updates and new articles.

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe now!

Subscribe

Erin Curry

Erin Curry