Let’s Be Clear: Risk Communication for Radiation Safety Professionals (Part III) — Provide Context to Help Readers Make Sense of Your Message

In Part I of this series, we

- defined risk and risk communication,

- discussed the need to consider the perspectives of your audience, and

- explored some of the barriers to effective risk communication.

In Part II, we explored how plain language can make your risk communication easier to understand and more effective.

In Part III, we will discuss the importance of providing context—additional information that helps to clarify meaning.

I used to think communication was the key until I realized comprehension is. You can communicate all you want with someone but if they don’t understand you, its silent chaos..

~ unknown

Context is like giving your readers clues to help them understand

In communicating risk as a radiation safety professional, often you have to communicate technical information to audiences that are not technical experts.

For you, concepts like dose threshold and rate of decay are simple and easy to understand. But these specialist terms can elicit anxiety and even fear for someone who doesn’t understand them. So, how can you convey your technical information in a clear and compelling way to people who are not radiation safety experts?

Clear communication always begins with your audience — consider their needs and tailor your message to make it relevant to them. When they need help understanding what you mean or the significance of what you’re saying, it helps to provide context. Perhaps offer a definition or include relatable analogies to illustrate what you’re talking about. Context can help your audience understand what the risk means and how it might affect them.

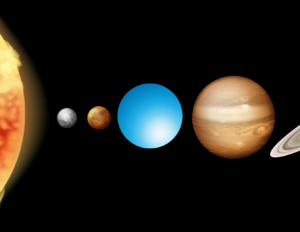

Let me demonstrate. When you look at this sphere, you can see that it’s round and blue, but what is it? How big (significant) is it? What is it used for? Without context, it’s hard to answer these questions.

So, let’s give it some context.

If I showed you the same sphere like this, do you have a better understanding of the size if this sphere?

How about if I showed it to you like this?

Or this?

The sphere itself is the same size, shape, and colour in all three illustrations, but the context provides additional information that helps you understand what the sphere might be and the scale of it.

Recommendations from the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) recognizes the importance of providing context “so that all readers can understand the issues easily.” [1] In REGDOC 3.4.1 (section 3.1.6), they acknowledge that, “when drafting content about a highly technical subject, you may be inclined to provide specialized information (such as regulatory limits or scientific formulae) to explain a situation.” However, “this kind of material should be discussed broadly . . . in a way that is meaningful to all readers.”

For example, they suggest that, when you are “including a unit of measurement, define the unit the first time you use it, and use that unit consistently throughout.” Then provide context to make the measurement more relatable. “Instead of only stating that, ‘. . . emissions are so many parts per billion (ppb),’ expand on this statement with language that is more commonly understood, such as, ‘. . . the emissions are 20 percent of the regulatory limit.’”

When you provide something like a measurement that a layperson might not understand, provide context (e.g., a definition, an example, a comparison) so that the reader can understand whether that measurement represents a significant risk or not. Try to use context clues that will be easily relatable to the person you are communicating with.

Examples from Bulletin contributors

Let me give you a couple of examples from past issues of the CRPA Bulletin.

Last year we shared a personal account that was originally written by Tanya Vlaskalin in 2011. In the article, [2] she described how she responded to a question she was asked following the Fukushima disaster. Someone she knew had family in Japan and was worried about exposure to radiation from I-131 contaminated tap water in Tokyo. The woman told Tanya “they found 200 Bq in the water,” and she wanted to know how worried she should be.

First, Tanya reassured the woman that we are all exposed to natural radiation in our environments every day. In fact, she said, there are natural sources of radioisotopes in our drinking water here in Canada. This was relatable context.

Next, she helped the woman make sense of the number she had been given (200 Bq in the water). She explained that Canada’s annual safety limit for ingestion of any isotope (including I-131) is 20 mSv. Then she provided some “simple calculations” that would help the woman understand how much risk 200 Bq of I-131 might present.

2 L (the amount of water international guidelines suggest we drink each day)

x 10 days (the amount of time that had passed since the accident)

x 200 Bq (how much I-131 was in the water)

= 4,000 Bq

Tanya explained to the woman that, “4,000 Bq would give an effective dose to the whole body of approximately 0.09 mSv.” In her article, she sagely noted for our Bulletin readers that the key was “relating the meaning behind the numbers.” Having explained that 200 Bq in tap water would result in an effective dose to the whole body of approximately 0.09 mSv, Tanya explained that lifetime risk of outcomes such as fatal cancer, severe hereditary effects, and non-fatal cancers from a single exposure to 1 mSv would be about 0.005% (according to the International Commission on Radiological Protection’s safety guidelines).

She went on to reassure the woman that this was a very conservative estimate. “We estimate 10 days, but I-131 has a half-life of 8 days, meaning the levels of I-131 are constantly dropping within the drinking water.” After providing the half-life measurement (8 days), she described what that meant (levels are constantly dropping).

In another article we published last fall, [3] Stéphane Jean-François was trying to help readers understand why a transport index has no units.

“An index has no units because, most of the time, it indicates a physical property that cannot be measured directly,” explained Stéphane. He used a couple of examples he knew his readers would have experience with — wind chill index and humidex.

Citing Environment Canada, he explained that “wind chill index and humidex are very much like a feeling. No instrument will read these indexes; instruments will only read the temperature, the wind speed, or the relative humidity of the air. . . If the wind blows at 65 kilometres per hour and the thermometer reads −22°C, the wind chill index will be −40, which represents ‘feeling like’ −40°C to the skin if there was no wind. Conversely, if the same thermometer reads 30°C and the dew point is 23°C, the humidex is 40, which feels very much like a tropical forest.”

Even if his readers never understand the scientific complexities of indexes, they will have first-hand experience with wind chill and so will be able to relate to his analogy. Stéphane goes on to define a transport index as “more a representation of a risk and a valuable ‘hint’ for people who would be clueless with or without a survey meter!”

Context is also a kind of hint that can help to bridge the gap between your expertise and your audience’s understanding. By clarifying meaning and providing relatable examples or analogies, context will improve comprehension and prevent miscommunication.

[1] REGDOC-3.4.1, Guide for Applicants and Intervenors Writing CNSC Commission Member Documents, pg 14

[2] “From the Archives—Fukushima and Me,” May 3, 2022

[3] “Indexes: Useful Clues for Laypersons,” October 11, 2022

Michelle Boulton

Michelle Boulton

Michelle is a clear communication specialist who uses clear (plain) language and design to help clients translate complex information into content everyone can use and understand. She and her team have been helping CRPA produce the Bulletin since 2007. For more information about Michelle, please check out her LinkedIn profile.

Do you want to read more articles like this?

The Bulletin is published by the Canadian Radiation Protection Association (CRPA). It’s a must-read publication for radiation protection professionals in Canada. The editorial content delivers the insights, information, advice, and valuable solutions that radiation protection professionals need to stay at the forefront of their profession.

Sign up today and we’ll send you an email each time a new edition goes live. In between issues, check back often for updates and new articles.

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe now!

Subscribe

Michelle Boulton

Michelle Boulton