Assessing Dose Administration of Lu-177 Dotatate Therapy: Quantifying the Residual Dose, Third Instalment

Résumé

Au cours d’une radiothérapie, le dotatate marqué au Lu-177 est typiquement dilué dans une poche de sérum physiologique, puis infusé chez le patient par intraveineuse. Une fois administrées, la poche de sérum physiologique et l’intraveineuse sont rincées pour s’assurer que la dose résiduelle soit administrée au patient. Toutefois, changer le sac de perfusion dans une seconde poche de sérum physiologique augmente le risque de contamination. Christian Detlef Raharja voulait savoir si le fait de rincer l’intraveineuse après la radiothérapie au Lu-177 améliore l’administration d’une dose ou si le fait de jeter l’intraveineuse et la poche de sérum physiologique constituerait une meilleure pratique.

Cet article sera présenté en trois segments. Dans le premier segment, l’auteur décrivait sa question et son hypothèse de recherche. Dans le deuxième, il en rapportait les procédures et les évaluations. Dans ce segment final, l’auteur discute des résultats de sa recherche.

by Christian Detlef Raharja

With contributions by Edward Sun, Judy Gabrys, and Rebecca Wong

The Michener Institute, University of Toronto

Background

When conducting Lu-177 therapy, the Lu-177 dotatate is typically diluted in a saline bag and then infused through an intravenous (IV) line to the patient. After administration, the saline bag and IV line are flushed to ensure the residual dose is administered to the patient. However, changing the infused bag to the second saline bag increases the risk of contamination. The author wanted to know if flushing the line after Lu-177 therapy improves dose administration or if discarding the line and saline bag would lead to better practice.

This paper is presented in three instalments. In the first instalment, the author described his research question and hypothesis. In the second instalment, he described the procedures and evaluations. In this final instalment, he discusses the results.

Results

After administration of the Lu-177 dotatate, a photograph was taken of the chamber. That photograph was compared to the volume scale used to estimate the volume in the chamber (see Figure 6 in the second instalment).

Table 2: Estimated volume remaining in the chamber and average residual activity after administration of the Lu-177 dotatate.

| Number of Cases |

Volume in the Chamber | Average Residual Activity |

| 17 | 0.00 mL | 4.49 |

| 6 | 4.25 mL | 8.32 |

| 2 | 8.50 mL | 9.99 |

| Total = 25 |

Later in the project, we discovered a way to completely empty the chamber. We attached the patient’s saline bag to the IV pump along with our Lu-177-infused saline bag, then clamped the IV line above the patient’s saline bag to ensure nothing was left in the IV chamber at the end of the administration. As a result, there was no volume left in the chamber in 10 additional cases.

Figure 8: Volume of Lu-177 dotatate and saline remaining in the chamber and the residual activity after administration of the Lu-177 dotatate.

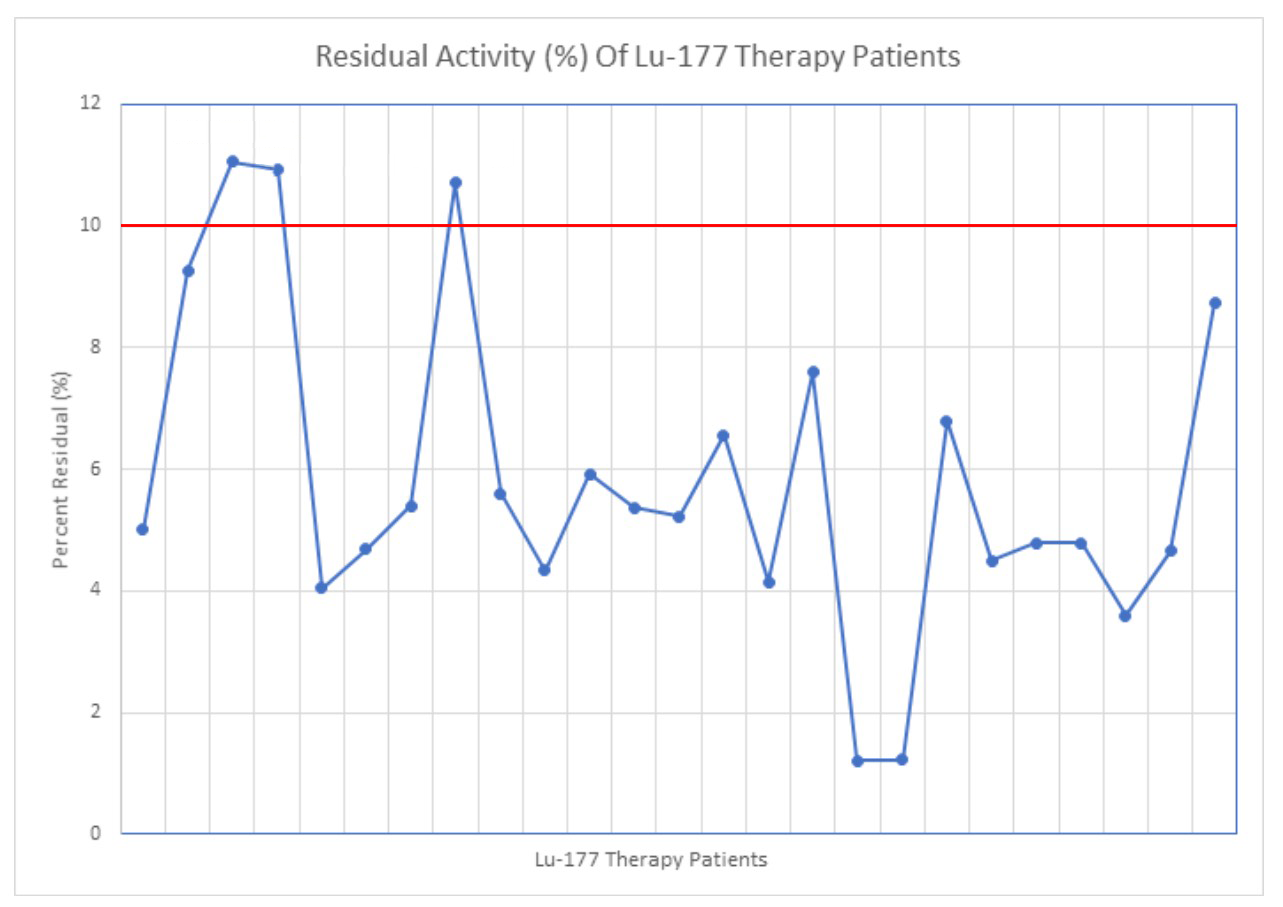

After conducting a bivariate Pearson correlation coefficient test, we found a significant correlation (r = 0.97) between the residual dose left in the chamber and the residual dose activity. Converted, the p-value was < 0.00001 (p < 0.05). An upper-tailed Z-test score was −19.9, which led to a p-value of < 0.05 (Figure 10).

![]()

![]()

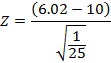

Figure 9: Upper-tailed Z-test calculation of the residual activity of the Lu-177 therapy cases.

The average residual dose from the IV line was below 10% (6.02% ± 2.85%) in the 25 cases measured (Figure 10). There were 22 cases that were under the 10% limit of the study and three cases that exceeded the 10% limit. In the three cases that exceeded the limit, there was more than 4.25 mL remaining in the IV chamber.

Figure 10: Residual activity of the Lu-177 therapy cases, calculated by assaying the activity in the line and dividing that by the total dose.

Discussion

Our project determined that there was a significant relationship between the volume left in the chamber and the residual activity left in the line. While the remaining volume is measured by visually comparing what is left in the line to the volume scale, the measured data supported our predictions. As such, the volume scale we developed could be a reliable predictor of the percentage of activity remaining in the line.

Our results suggest that if the saline bag and IV line are not flushed, the volume remaining in the IV chamber should be less than 4.25 mL, which would ensure the activity left in the line is than 10%. This would imply that after administering the Lu-177 dotatate through the infused saline bag, one could discard the bag and line without flushing.

Eliminating the flushing step does present a slight risk of under-dosing the patient. In most cases, the residual activity was less than 10% of the administered dose, but we did have some cases where the residual dose was over 10%.

We discovered that clamping the saline bag (which is also on the infusion pump) allows the fluid in the chamber to be completely administered to the patient. If the remaining volume in the IV chamber is 4.25 mL or more, the saline bag should be clamped (as described above) or the IV line should be flushed with a new saline bag.

Skipping the flushing step would also decrease both treatment time and wait time. The added step of flushing the IV line and chamber prolonged the dose administration by nearly 10 minutes on average (Figure 11). When the IV line and chamber were also assayed, it took even more time, almost 18 minutes on average (Figure 11). Patient beds are limited and patients usually have to line up to get into the hospital. This additional time meant patients had to wait longer to be admitted.

Figure 11: Extra time (in minutes) taken to complete the extra steps of flushing and assaying the IV line and chamber.

The risk of contamination also increases when flushing is needed. Kumar et al.[1] described how contamination can result in excess radiation exposure to patients and staff and hinder the workflow of technologists. Early in our project, contamination resulted when a small amount of the residual dose spilled on the injection table when we were flushing the Lu-177 dotatate from the IV line. (See Figure 2 in the second instalment.) As a result, we had to decontaminate the table and then store the table in a lead-lined room. If a drop were to land on the patient, added measures would have to be taken to ensure the patient’s safety.

Since contamination could result in excess radiation exposure to everyone involved in the trial, eliminating the flushing is even more justified, especially as the dose administered was high (approximately 7.4 GBq).

Contamination also presents the possibility of a false positive. In our study, the injection table was contaminated, but if that droplet had landed on a patient’s gown or another area on their body, a false positive might have resulted when the patient was scanned (approximately four hours later).

Conclusion

Our results indicate that the residual dose remaining in the IV line is not significant and flushing is an unnecessary step for Lu-177 dotatate therapies. Eliminating this step would decrease the risk of contamination and increase workflow efficiency.

Limitations

We identified several limitations to our study.

After administration of Lu-177 dotatate the volume within the IV chamber might vary. This volume cannot be altered after the administration and can only be eliminated through flushing. A volume scale was created to estimate this variance, but the scale was compared subjectively against a photograph, which was a limitation due to variability in categorization.

Another limitation was the chamber photograph, which could have been taken at different angles, resulting in variation in how the residual volume was approximated according to the scale. Taking the angle into account when taking the photographs limited the variation but did not eliminate it completely.

The sample size of 25 datasets may also be considered a limitation.

Future direction

Larger-scale research could further explore the question of whether flushing is necessary. If multiple hospitals collected data on the residual dose left in the IV line, we would have an increased sample size and a more significant study. Although our project concluded that flushing was not a necessary step, our sample size of 25 cases may not have been large enough to warrant changing the Lu-177 dotatate protocol.

Our project could also be used as a precursor to assess exposure rates when administering Lu-177 dotatate therapy. Conducting a study that specifically measures the exposure of the patient and technologist when the IV line is flushed and comparing it to the exposure when the IV line is not flushed could determine if there is a significant difference.

Erwin et al.[2] concluded that staff involved with Lu-177 dotatate therapy had a significantly higher exposure rate than those who were not involved the therapy. However their study could be expanded to check these rates when flushing is added as a step versus when flushing is omitted from the protocol.

1. Kumar, N., et al., 2017. Contamination, a major problem in nuclear medicine imaging: How to investigate, handle, and avoid it. Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology, 45(3), 241–242.

2. Erwin, W., et al., 2015. External radiation exposures from lutetium-177 dotatate therapy patients. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 56(3), 1246.

Christian Detlef Raharja

Christian Detlef Raharja

Christian Raharja is a nuclear medicine student at the Michener Institute, University of Toronto. His current clinical rotation is within the University Health Network, which includes Toronto General Hospital, Toronto Western Hospital, and SickKids Hospital. His work focuses on creating quality assurance projects to improve the current trials and procedures implemented in the hospitals he works in. His hobbies include weightlifting, cooking, paddling (dragon boat), and travelling.

Christian Raharja étudie présentement la médecine nucléaire à l’Institut Michener de l’Université de Toronto. Il effectue présentement son stage clinique au sein du réseau de santé University Health Network, qui inclut le Toronto General Hospital, le Toronto Western Hospital et le SickKids Hospital. Ses recherches sont centrées sur la création de projets d’assurance qualité afin d’améliorer les essais et procédures actuels mis en circuit dans les hôpitaux où elle travaille. L’haltérophilie, la cuisine, le bateau-dragon et les voyages font partie de ses principaux passe-temps.

Christian Detlef Raharja

Christian Detlef Raharja